I first started programming at age 10. I personally don't recall 'studying' programming languages formally. Most programming languages that I picked up, much like the five spoken languages I am comfortable with, I picked up by trying, tinkering, and applying them to solve real-world problems.

Lately, I've been mildly obsessed with the idea of learning new things. Recently, I learned how to juggle, I learned how to touch type, I learned how to play the piano and I learned how to drive a stick shift. Lessons learned from all of these adventures, translate well to learning something technical too – Whether you are learning how to play the piano or deep dive into machine learning, the basic steps to learning are the same 1) Break down a daunting topic into smaller topics; 2) Focus on one topic at a time and get the resistance out of the way to make practicing easy; 3) consistently learn every day – 20 minutes to an hour for a couple of months 4) profit.

However, when it comes to technical topics, apart from the steps mentioned above I've always followed a specific style of learning that works for me. I like to call this the Scattered Onion style of learning.

It's clearly something I did not invent (And ChatGPT tells me it's not even a real thing) but it is a style of learning that comes naturally to me.

Ask ChatGPT what the Onion style of learning is and it provides this explanation:

In some contexts, when people refer to the "Onion Style of Learning," they may be alluding to a layered or gradual approach to learning, where one starts with a basic understanding or foundation of a topic and then gradually adds more depth and complexity, much like peeling the layers of an onion. In this interpretation, learners start with fundamental concepts and build upon them as they gain proficiency and expertise.

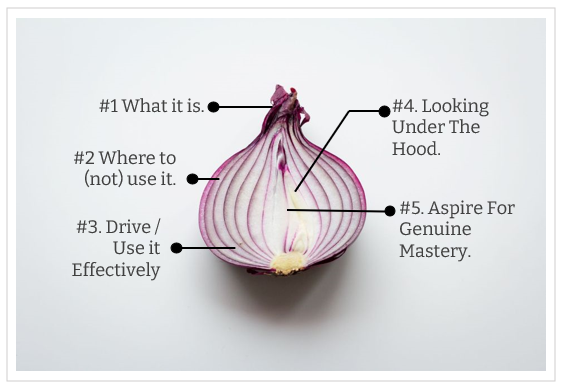

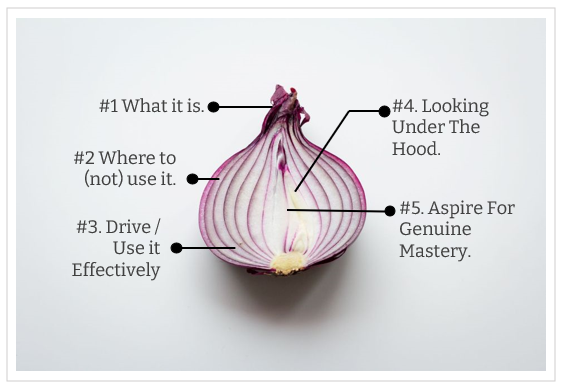

When I want to pick up a new topic, the steps that I follow are structured and simple. Every time I effectively end up learning a new topic I find myself repeating these steps. Each step is like pealing a layer of an onion. The steps/levels/layers of learning are:

Level 1: The Conceptual Layer – Answering The "What It Is" Question

For me this is foundational. I respect folks who can reach chapter 1 of a technical topic and move on to chapter 2. For me, the ground-level familiarity of a subject is much more important. This is very similar to the Feynman Method of learning where you a) pick a high-level topic b) understand it and try to explain it like you are teaching it to a child c) review and refine that understanding d) document that explanation and revisit it frequently.

Put simply, when I am picking up a topic my first attempt or layer of learning involves understanding what the topic is about. Take, for instance, Machine Learning. If you are reading this take a pause and try and answer the question "What is Machine Learning?" – not with the intention of answering the question, not with the intention of convincing someone that you know what it is, but really answering the question with the level of insight that will explain all the complexity of machine learning to a 12 year old who will just not be intimidated by technical jargon and will keep on asking you questions till they understand.

And no, a lame answer like Machine Learning is where machines can think like humans, does not qualify simply because you are explaining a complex topic to a 12-year-old. I've tried this with so many programmers and when I start asking them questions on some of the simplest topics, their explanations often start to break down. Most programmers today cannot answer fundamental questions like What really is object orientation, or what are interfaces; or even how simple loops work; not because they don't have an intuitive grasp but because they have never really given the question much time to think and develop their own insights to explain it simply. I don't blame them for it. Simplicity is hard. Understanding something in a way that you can explain it simply is harder.

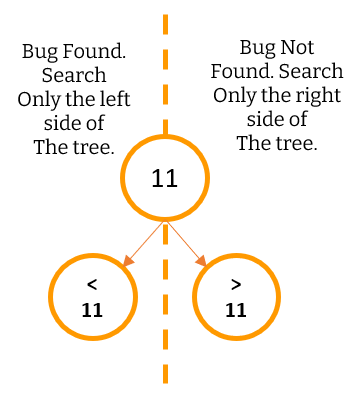

Level 2: Where To Use It And More Importantly Where Not To Use It

After you can explain what something is, the goal is to take your understanding to a level where you not only know where to use the technology but where not to use it. After all, when the only tool you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. There are countless people (even really senior folks) who go completely blank in my interviews when asked the most fundamental questions about where you should not use a tech. For instance, a candidate who goes on and on about the Actor Model – starts fumbling all over the place when you ask them when they should not use actor-model or when someone is listing the benefits of messaging and you ask them to talk about a couple of situations where message queues are a bad idea. Again, I don't blame them for this. In today's world where we are all in a rush to pick up the next big thing, pondering about where it should not be used seems like a waste of time. But in reality, if you consider yourself a technologist, where not to use a tech, is as important as where you should use a technology.

Level 3: Drive The Car (Use the tech competently enough)

If you've ever driven a car hardly ever open the hood, you know exactly what I am talking about. Most programming languages have their nuances. But to start using them you don't need to know the nuances. You just need to know enough so that you can start using them. This is your gateway into mastery – because once you start driving the car a lot, sooner or later you may have a flat tire and may have to learn how to replace the tire; which over a period of time will make you wonder, how the hell does the wheel really work and why it took mankind 200,000 years to invent the freaking wheel? As you get familiar with a framework or a language you start asking questions like "Huh! I wonder how that works?" – but that comes later – In most cases though, you can simply be a good enough driver and still get from point A to point B. As the creator of the C Programming langue Dennis Ritchie is said to have put it:

The only way to learn a new programming language is by writing programs in it.

It's not true for only programming languages but for anything. Spoken Languages, driving a car, writing a book, playing a musical instrument. You become good at most things by not just learning, but doing them and actively engaging with them.

Level 4: Look Under The Hood – An Intuition about The Internals

Once you get sufficiently good at a tech, programming language, or platform and have used it enough you are bound to hit a few hiccups. You might come across JavaScript doing some pretty funky stuff for instance and you may be curious about what is going on. This is like changing the spark plug or your car, being able to replace the tire, or reading about the basics of a combustible engine.

Most people will stop at this level. I suggest you do too. Being at this level will put you way above most of the crowd, will end up making you look really smart (which may not be relevant), and will make you hugely productive (which is relevant). The good thing is, you can be at this level with a LOT of different topics and things. That will also allow you to connect the dots from other fields and draw learnings from completely disconnected things. Going any deeper, unless you are really passionate about a specific tech is a waste of your time.

Level 5: Inch Towards Mastery – The Ability To Make Your Own Car

This bit comes organically after years of commitment and most people don't really need to worry about this in all fields other than one of their own choosing. This is where you make a contribution to a Linux Kernel because you don't agree with the way it does memory management or you write your own language because you feel that none of the languages out there fit your requirement. This is where papers are supposed to be written, genuine patents are supposed to be filed and larger contributions are made to the community. This is a stage where you don't just drive a car or fix it's components, but can design and build your own cars. Mastery comes at a price so be very selective about topics where you want to achieve world class mastery.

The Central Idea Behind Stages

What's important to note here is that these are all different stages of learning. At every level, you are not learning new topics. Instead, you are going deeper into the same set of topics you started off with but are literally "digging deeper". So, if your topic was the Rust programming language – you would start off with: Layer #1: What is Rust? Layer #2: Where Should I use it and where should I not use it? Layer #3: How I can write a couple of system utilities using it? Then proceed to write a few low level utilities using it! Layer #4: Finally understand the nuances of the language – for example how the Borrow Checker really works.

Once you have done all of these and looked under the hood for a sufficiently vast array of topics connected to Rust, give yourself a pat on the back or a nice little intrinsic reward, consider yourself at level 4, and move on to the next topic. Level 4 is where you want to stop for most topics.

If you genuinely love the topic, you can take steps towards deliberately spending another 10,000 hours on it, and you will eventually achieve mastery in it – but pick that topic wisely because you don't have infinite time on this planet.

Approach And Process

For me personally, when it comes to layered learning, Approach that I take and the process that I follow is also equally important. Each person is different. These are a few other important tips work really well for me:

#1 Be Scattered - There are lots of folks who like to start one thing, finish it, and only then move on to the next thing. I respect these people. Power to them. My mind however is not that disciplined and structured. Being scattered is fundamental to my learning. On any given date I might be doing research on encryption algorithms for a patent disclosure, working on improving my lousy chess skills, learning Rust, dabbling with building a recommendation engine using a neural network, reading a deep psychology textbook and writing about what I learned from reading fictional story. On any given date, I have over a dozen threads open to choose from. Being scattered means that you are never bored. And you never have to force yourself to learn one thing. Don't feel like going deep into Gradient Descent? You can just have fun learning the complexities and variations of the Sicilian Chess Opening today and come back to Gradient Descent tomorrow.

Being scattered and having multiple threads of items always open means 1) you're never bored, 2) you never have to force yourself to pick a topic you don't like on any given time - you have a variety of things to pick from based on what you feel like working on that day and 3) as your interests evolve there is a democratic election of ideas that compete for your attention based on what you love doing where the best ideas or the ideas you are most interested in eventually win, which means a more fun filled life. There is a lot to be said about the science of being scattered. It is a whole new post in itself.

#2 Be Intentional – For me, when something gathers my interest and I decide to give it precious hours of my life, I must decide up front how many layers of that metaphorical learning onion I intend on pealing. So if you are starting to learn the piano at age 40, aiming for level 5 and aspiring to become a professional pianist may be an impractical idea. Being able to play a simple song by ear? That's a much more practical goal. Before you start learning how to play the piano, you know that you want to get to level 3 and then once you are there, you can either continue to stay there as a hobby and inch forward slowly for fun or just quit and move to something else.

#3 Be Mindful Of Diminishing Returns: In most things, 40 to 60 hours of deliberate practice will get you to level 3 which is when the laws of diminishing marginal returns start to kick in and unless you are really serious about the topic, it's time to drop out or just stay at that level for fun or effective productivity. There are a lot of people who know how to drive a car but know nothing about the mechanics of a car. They spend their life happily staying at level 3, without ever looking under the hood. Of course, if you are genuinely interested in the topic you can always probe deeper, but at every step it's important to be intentional about what you are trying to achieve. Once you are at level three every step forward requires considerably more effort. The fight against diminishing marginal returns is worth it, only for topics that you absolutely love.

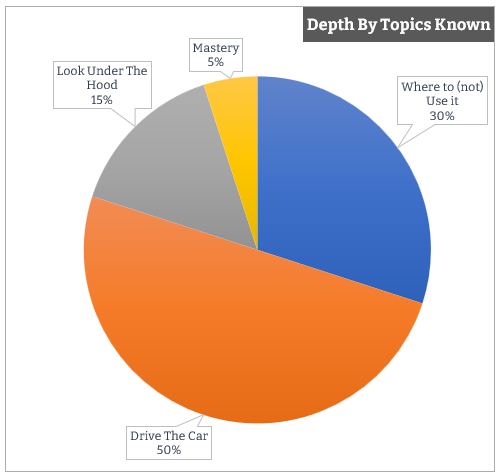

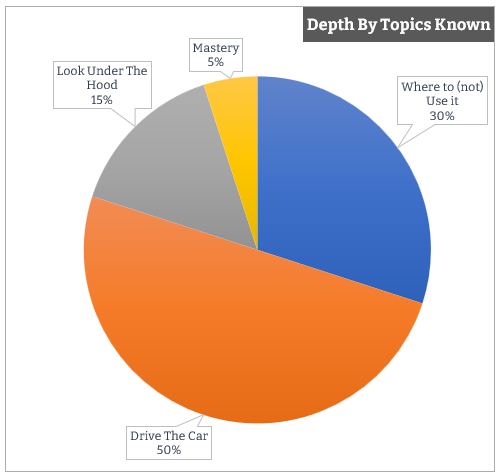

#4 Define Your Learning Portfolio – What is your role? What do you do for a living? How important is depth for you? How important is breath? That decides your depth portfolio. For example, I work as a professional software architect. For me understanding a vast variety of tools, frameworks, and technologies is really important. As of today, if I list down all the topics in my resume and make a nice little pie chart of what my portfolio looks like it would look like this:

At any given time, when I am picking up things; 30% of my knowledge base is at level 2. I'm constantly reading about new technologies and frameworks being released, finding out what is new, what the tech does, why I should know about it, where I should use it, and where I should not use it. Not everything I read requires probing deeper than this.

Another 50% of my knowledge portfolio sits at level 3 – I can productively use the framework, write code, and solve real-life problems with it but I may not ever look under the hood actively (unless I want to solve a specific problem for which I am forced to).

The other 15% is where I am at Level 4 – where I am actively looking under the hood – and there are only 5% of the topics where I have a desire to get to a master's level. These are topics I've been reading about, engaging in and actively participating in for over 15 years, and have no intentions of quitting. I'm not saying your portfolio might be the same as mine, but it's important to know what your learning depth across topics looks like and that you be intentional about it.

The most common pushback I hear from folks when it comes to the topic of learning something new, pursuing a hobby or just being curious about topics is – "I don't have time". With layered learning you don't need a lot of time if you are intentional about which layer you want to operate in for any given topic. For example, it hardly takes 1 to 5 hours to peal the first layer of the metaphorical learning onion for any given topic and get to level 1. Have a couple of dozen learning threads open in your life, intentionally select the level you want to be on each thread and every day just pick anything from those dozen threads that you feel like studying on that day; give it an hour. That is all you need. The topic can be anything. Whatever you feel like picking up from a pre-decided list of topics you have on your list. Don't feel like going deeper on that topic the next day? No problem, pick something else from the list and come back to this topic whenever you feel like it. Once you get into scattered layered learning, picking something new will never feel like a chore again. It'll be fun, engaging and the resistance should lower considerably. Plus you'll start going deeper into topics that you genuinely care about. Go pick something new to learn and try to peal a few layers of the metaphorical learning onion. I wish you good luck.

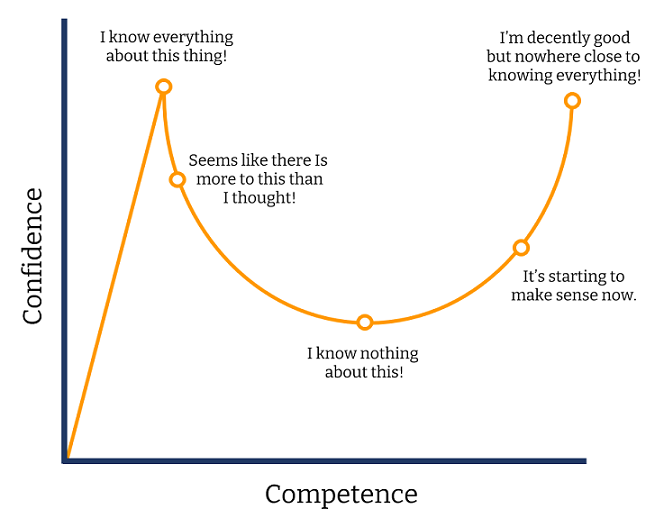

This is why as people become better at any craft their self rating in that craft keeps coming down. The less you know the craft, the higher you rate yourself in it. The more you know the craft, the more you know what you don’t know and the less you rate yourself.

This is why as people become better at any craft their self rating in that craft keeps coming down. The less you know the craft, the higher you rate yourself in it. The more you know the craft, the more you know what you don’t know and the less you rate yourself.

Comments are closed.