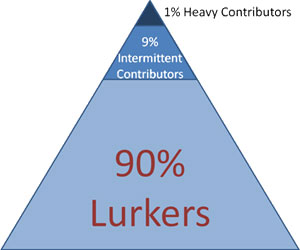

Jakob Nielsen in his classic article on participation inequality describes what he calls the lurker's pyramid using this simple diagram:

Even more depressing than the diagram, are the statistics that Jakob provides in the article. He explains:

There are about 1.1 billion Internet users, yet only 55 million users (5%) have weblogs according to Technorati. Worse, there are only 1.6 million postings per day; because some people post multiple times per day, only 0.1% of users post daily.

Blogs have even worse participation inequality than is evident in the 90-9-1 rule that characterizes most online communities. With blogs, the rule is more like 95-5-0.1.

Inequalities are also found on Wikipedia, where more than 99% of users are lurkers. According to Wikipedia's "about" page, it has only 68,000 active contributors, which is 0.2% of the 32 million unique visitors it has in the US alone.

Wikipedia's most active 1,000 people - 0.003% of its users - contribute about two-thirds of the site's edits. Wikipedia is thus even more skewed than blogs, with a 99.8-0.2-0.003 rule.

Participation inequality exists in many places on the Web. A quick glance at Amazon.com, for example, showed that the site had sold thousands of copies of a book that had only 12 reviews, meaning that less than 1% of customers contribute reviews.

Furthermore, at the time I wrote this, 167,113 of Amazon’s book reviews were contributed by just a few "top-100" reviewers; the most prolific reviewer had written 12,423 reviews. How anybody can write that many reviews - let alone read that many books - is beyond me, but it's a classic example of participation inequality.

As programmers like to think of and fantasize about the web as this amazing medium of delivering content which allows two way communication. We go out an pass generic statements, like 'today anyone who wants to make a difference can make a difference' and then we go out there an nudge the lurkers and the leaches to come out and participate.

Jackob however has a different opinion. Instead of trying to alter the basic behavior pattern of a lurker, Jakob suggests a variety of techniques for getting feedback from lurkers in the article. Some of these techniques are really interesting. Think of the people-who-bought-this-also-bought-Amazon-feature for instance, where the mere behavior of the lurker: the act of buying a book for instance, actually acts as a feedback for others. Smart.

You may not be able to change the fundamental behavior pattern of a lurker overnight just by nudging him to participate or contribute. You might be able to make him publish a blog post or have him comment on one, but be rest assured that if you are targeting a lurker and expecting him to change he will hide back in his cave again, faster than you can think.

It is a painful reconciliation and an insight that you gain with time, but irrespective of what you are trying to do, building a community, promoting a product, service or an event, your only chance of converting lurkers into participants is by letting them hang around, making them comfortable, making them believe that no-one is watching them, making it really easy for them to get involved in tiny little ways if they want to and most importantly, having them keep coming back.

If they do stick around for long enough or keep coming back every now and then, chances are that some day, you might actually touch them, connect to them or even rub them the wrong way. This is when they might slowly and reluctantly take the leap from being a lurker to an occasional contributor.

If you are reading this and you are a lurker who has never commented here, it's okay. Just keep coming back and some day, we just might 'connect'. Some day we might have a discussion over a blog post that inspires you, moves you or maybe just pisses you off really badly.

Till then, happy lurking.

I wish you good luck.

Comments are closed.